Mon, 01/30/2017 - 08:03 by karyn

“To battle somebody, to fight somebody, it’s not about doing something for yourself. Everyone has to understand what’s you’re doing.” – Mr. Freeze, for ARTE Creative’s webserie “B-Boys: A History of Breakdance”

Breakdance has been celebrating freedom of expression and athleticism alongside hip-hop culture ever since its breakthrough back in the 70’s. The term “B-boy,” introduced by famous Jamaican-born DJ and innovator of hip hop culture DJ Kool Herc, refers to “break boy.” The reason for this was simple: the many dancers would wait for the “break part” of a song. Little did he know, Kool Herc would set the terminology for years to come.

Emerging from the Bronx, New York, along with other hip hop related movements, B-boying manifested a wild urban spirit as young artists were striving for a better life; trying new things because they could. The desire to challenge the system in a whole new way was very present. Long story short, B-boying had its first downfall in popularity in the USA shortly after 1988. Nonetheless, the craze for the dance movement had already picked up in Europe. In 1991-1992, the German crew Battle Squad - Storm and Swift Rock - went over to New York where the breaking had considerably slowed down. Bringing to life a second wave of B-boying, the movement was then kept alive through many videos and worldwide jams. With time, the subculture spread almost everywhere it could and today, B-boying has been used in mainstream culture numerous times — movies, TV shows, commercials… you name it.

Taku Obata is not your regular type artist. Born in 1980 in Saitama, Japan, where he is currently based, he grew up with B-boying. Obata was even one of the founding members of a B-boy crew, the Unityselections, in 1999. In 2008, the Japanese artist received a master’s degree in sculpture from the Tokyo University of the Arts and won, that same year, the grand prize at the Tokyo Wonder Wall Grand Prix.

Using the ancient technique of Japanese woodcarving, Obata intertwines popular culture with his roots. In this technique, the artist starts off with a soft wooden block and chisels his way through the matter following a drawn pattern. This kind of woodcarving requires the sculptor to master freehand work. Much like B-boying, practice is key, and power of expression along with freedom of movement are of the highest importance.

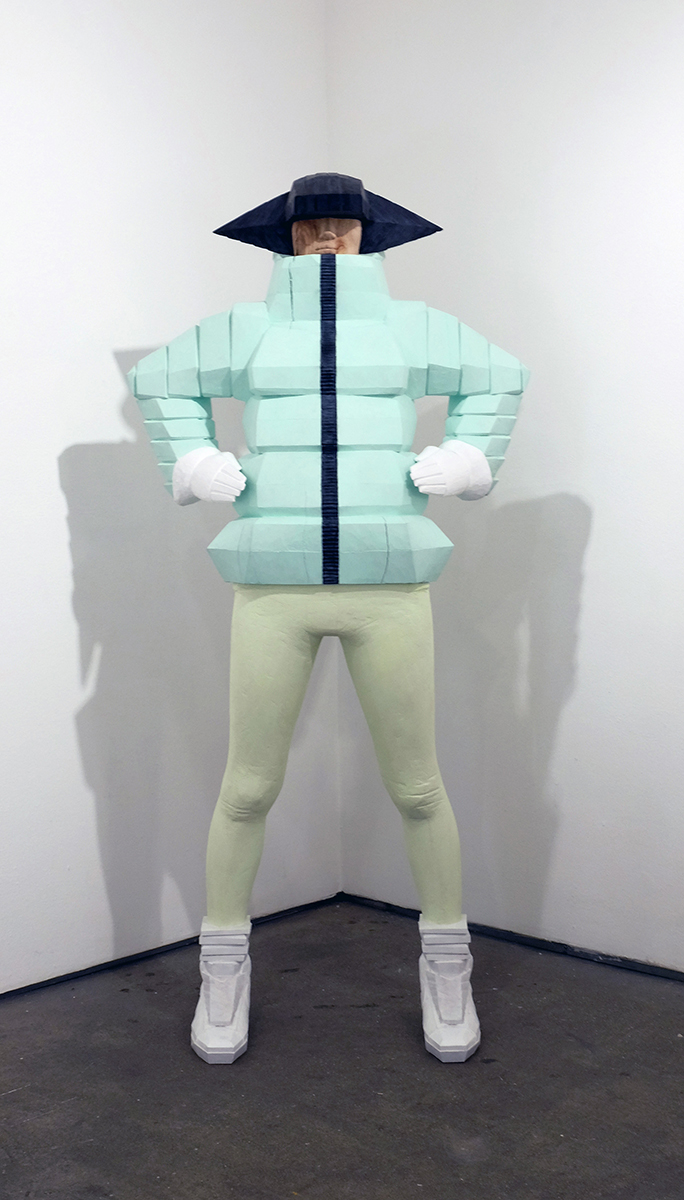

About two years ago, Obata, a B-boy himself, was in New York showcasing his debut solo exhibition “Bust a Move” at the Jonathan LeVine Gallery. With such a title, the exhibition had to have something to do with dancing and movement. It turns out it's exactly Obata's main artistic inspiration. Fully immersing viewers in the subculture he’s been evolving in for the past 18 years, the artist’s work is an attempt at enhancing our physical senses and awareness. The wood carved sculptures he creates are all B-Boys striking a pose and “freezing for the camera” — the public’s eye. But Obata does “not simply create a B-boy, but aims to create an atmosphere, a cool space with a certain strange and unusual tension.” And who could better understand and reproduce a hip hop dancing ambiance than a dancer himself?

Fundamentally, what makes Obata’s sculptures so outstanding is his precise comprehension of body kinetics and rhythmic contortions B-boys are expected to perform. Originally, B-boy moves were composed of many gestures meant to humiliate the opponent being battled. In the 1970’s, it was a way of calming the craziness going on in the streets. B-boys were expected to have style, character, and originality. Stealing moves from another B-boy was unthinkable and so the quest to find a unique movement established a constant desire to reinvent things. Possibilities were infinite. The inspiration for dance moves came from many different backgrounds and cultures including kung-fu movies, Capoeira and African dances. Obata’s sculptures, wearing bright and colored jumpsuits with accessories representative of the old school B-boy style, suggest a profound research on kinetic energy. The elongated hats, glasses and gloves create an illusion of movement contrasting with the subjects quiescent state.

The Japanese artist works in a way that gives the viewer an impression of looking at a long-exposure photograph. The B-boying movements — top rock, down rock, footwork, freezes and power moves like windmills, air flares, handglides, shoulder glides, backspins — seem to have no secret to him. The challenge resides in every bit of matter he carves out of the original wooden block. For him to create the perfect illusion of a frozen-in-time B-boy, there’s no room for error — the same as if in an actual battle. The carver’s slightest hesitation could result in an unrealistic sculpture while any hesitation from the part of the B-boy could result in a battle loss. Sculpture and B-boying may be two entirely different worlds, but Taku Obata creates his own path and makes sure both his worlds become one.

Facebook: taku.obata

Add comment